If you want to learn a musical instrument and you have never learned one before, chances are that people will recommend you learn e.g. the recorder (flute) before learning the saxophone or the trumpet. The recorder is simple, but not so simple that you cannot learn something about rhythm, notes, tonality and the mechanics of playing a woodwind instrument, along with enjoying the feeling of success that comes with being able to play a familiar melody on an instrument.

The same argument can be made for languages. There are languages that are easier and languages that are harder, so if you are currently trying to learn a language deemed 'hard' and it's doing your brain in, you may want to try an easier language - not to abandon your chosen target language, but to learn some concepts in an easier form before tackling them in a harder form. Even a few hours spent on an easier language can help you make faster progress in your chosen target language. In the case of Esperanto, which is perhaps the easiest human language, various studies have shown that the effect of learning Esperanto is so pronounced that it makes up for the extra time spent, e.g. students who spent one year on Esperanto and then three years on French ended up with a better command of French than those who had studied four years of French. Why? I will give some reasons below.

Grammar

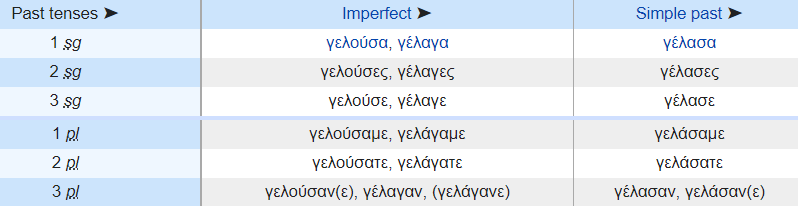

Different students have different pain points, but grammar is pretty consistently named as a source of difficulty. Some languages have very extensive grammar while others have simple grammar. For example, imagine that you want to say "he laughed". In Greek, you'd be squinting at this:

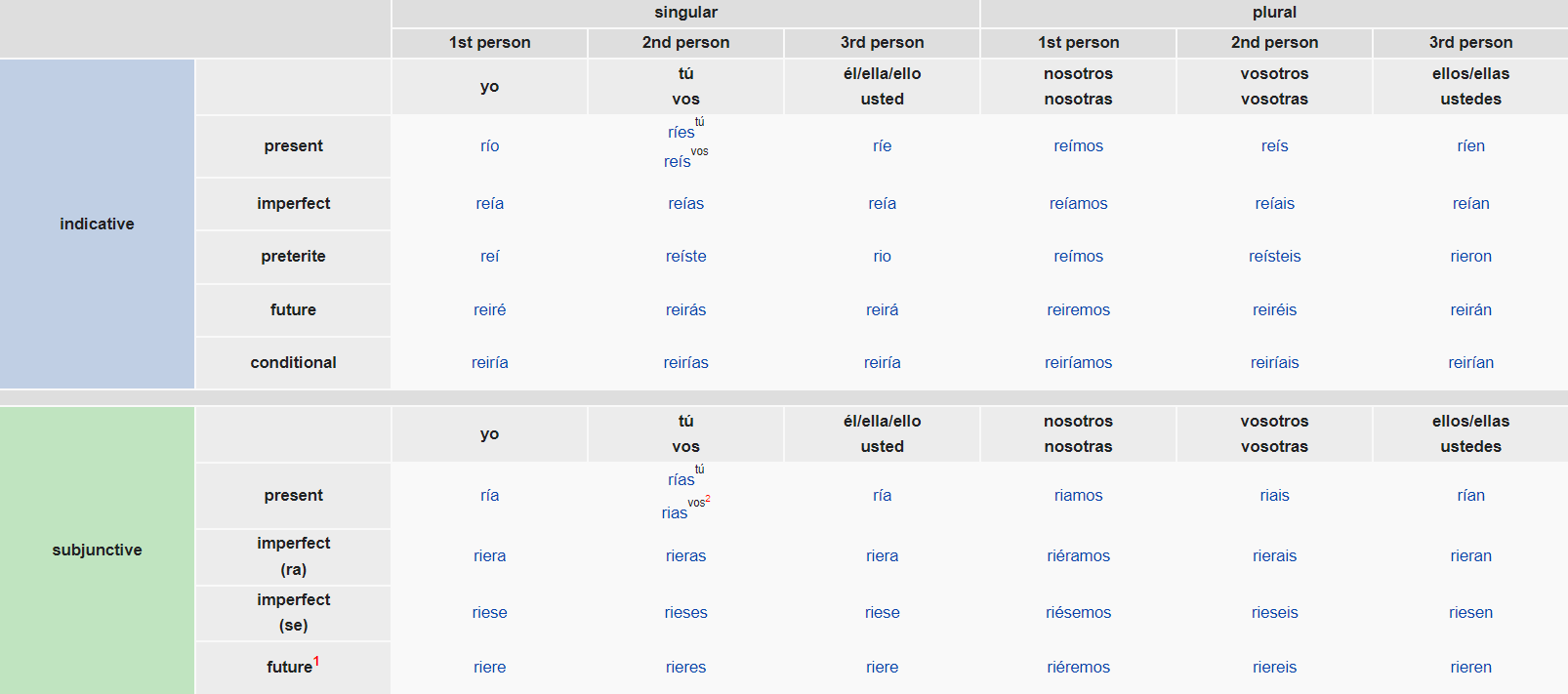

In Spanish, you'd find this:

While in Esperanto, there is only one possible form.

If you're learning French, there are less (currently-used) forms to learn than in Spanish, but there are more exceptions than rules. Even French native speakers often have to refer to a grammar book for those. In Esperanto there are no irregularities.

In Esperanto, when you're talking about the present, you always use the ending -as:

mi ridas (I laugh / I am laughing)

li ridas (he laughs / he is laughing)

When you're talking about something in the past, you always use the ending -is:

mi ridis (I laughed / I have laughed / I was laughing)

li ridis (he laughed / he has laughed / he was laughing)

As you can see, the -as stays -as and the -is stays -is. As you can also see, there is only one way of talking about the present and only way of talking about the past, unlike in English, which introduces artificial differences like "I laughed" vs. "I have laughed" vs. "I was laughing". Esperanto can help you become comfortable with the idea of tenses and of verb endings... without dumping a whole table of them on you, plus a long list of exceptions. This doesn't just mean it's faster - it also allows you to focus on the essentials. If you imagine a story about something that happened in the past, and you keep seeing -is, -is, -is, -is, that's more striking than when it's -ia one time, -ado the next time, -iste the third time...

If your target language has cases (e.g. German or most Slavic languages), you'll be particularly happy for this, because the idea of cases is quite hard to grasp for English speakers. Esperanto only has the Accusative and it always ends in -n, even in plural and even for personal pronouns, so after studying two weeks of Esperanto, you'll have a better grasp on the function of the Accusative (and on cases in general) than after two MONTHS of Russian.

Vocabulary

Apart from learning grammar, you also have to get used to foreign vocabulary. Most importantly, you have to get used to the idea that foreign languages use words differently and that there is no 1-to-1 mapping of words. You also have to figure out how to memorize vocabulary and how to retrieve it during conversation. These are basic abilities that you don't necessarily have if you're not yet fluent in a single foreign language. Esperanto can be a good way to acquire these abilities without being weighed down by the amount of stuff you have to learn. In Esperanto, you can have basic conversations much sooner than in other languages because there is so much less grammar and because there is also less vocabulary. A lot of Esperanto vocabulary is simply the same word with a different ending or with something attached to it. All in all, in order to reach the same level of fluency in Spanish and Esperanto, you'd need 5000 Spanish word roots but only 500 Esperanto ones.

These things that attach to words (prefixes and suffixes, collectively called affixes) are a major discovery when it comes to learning languages, so much so that I've written an entire blog post just about them. If your target language is Spanish, Italian, French, Portuguese or German, you will benefit from Esperanto's stock of Romance and German word roots that will be a nice foundation for acquiring these languages later. However, if your target language is Hebrew, Arabic, Chinese, Japanese, Indonesian, Swahili or any non-European language, you will benefit from understanding the universal system that determines how humans create vocabulary, and there is no language better suited to teaching you this system than Esperanto. It is the only language that has this system in pure form - applying it 100% all the time to everything, without exceptions or "we don't say it that way".

Practice

It is said that the second foreign language is easier to learn than the first, the third is easier to learn than the second, the fourth is easier than the third... each language makes it easier to learn another, because you're getting better at learning languages itself. All those minor skills like being able to understand grammar features, to memorize vocabulary, to master a foreign prosody, to apply a foreign language filter to your thoughts before speaking, and so on, all skills start from near-zero, they are significantly better after learning one foreign language than after zero, and then they continue to improve at a slower pace with each foreign language you add.

This means that there are many transferable skills and it is possible to get better at language acquisition in the abstract and then use this in order to better learn any other language you want to learn. If your goal is to learn a language that is widely regarded as difficult, e.g. Japanese or Korean, then having higher language acquisition skills will help you make progress faster and be less frustrated than someone whose language acquisition muscles are completely untrained.

Another analogy: if you're planning to climb a mountain, it helps if you're not a couch potato suddenly trying to climb a mountain but if you've done other sports. That is not to say that couch potatoes absolutely need to take up cycling or weight-lifting before training to climb, but the difficulty of some sports is such that newbies may need so much time and effort to get anywhere worthwhile that most will get discouraged beforehand.

Same for languages: the difficulty of some languages is such that newbies may need so much time and effort to get anywhere worthwhile that most will get discouraged beforehand. There are people who have mastered difficult languages without having studied any other language, but the amount of time and effort involved is insane. I recommend studying at least the basics of Esperanto in order to learn essential concepts and build up those language acquisition skills, after that it will require a lot less time and effort to achieve a good level in a harder language.

Next steps

If you're convinced, my top 3 ways to learn Esperanto are:

1. Teach Yourself Complete Esperanto (book with free audio), which will bring you up to B2 (upper intermediate) level, with a particular emphasis on conversational ability.

2. If you only want get a taste, I recommend the free course at Lernu.net .

3. My least favourite is the Duolingo Esperanto course. It's a good course, more gamified and possibly more fun, but Duolingo did not allow course creators to display explanations of the grammar and word creation system, so you're missing out on a lot of the things that make Esperanto such a help in learning other foreign languages.

Esperanto is not just a tool to learn other languages though. You can actually use it to talk to people with whom you have no other common language (I did so in Japan), read original works of literature, listen to music, go to festivals, travel more cheaply, and so on. Here's a list of useful links for those who have just completed a basic Esperanto course.

Good luck in your studies!