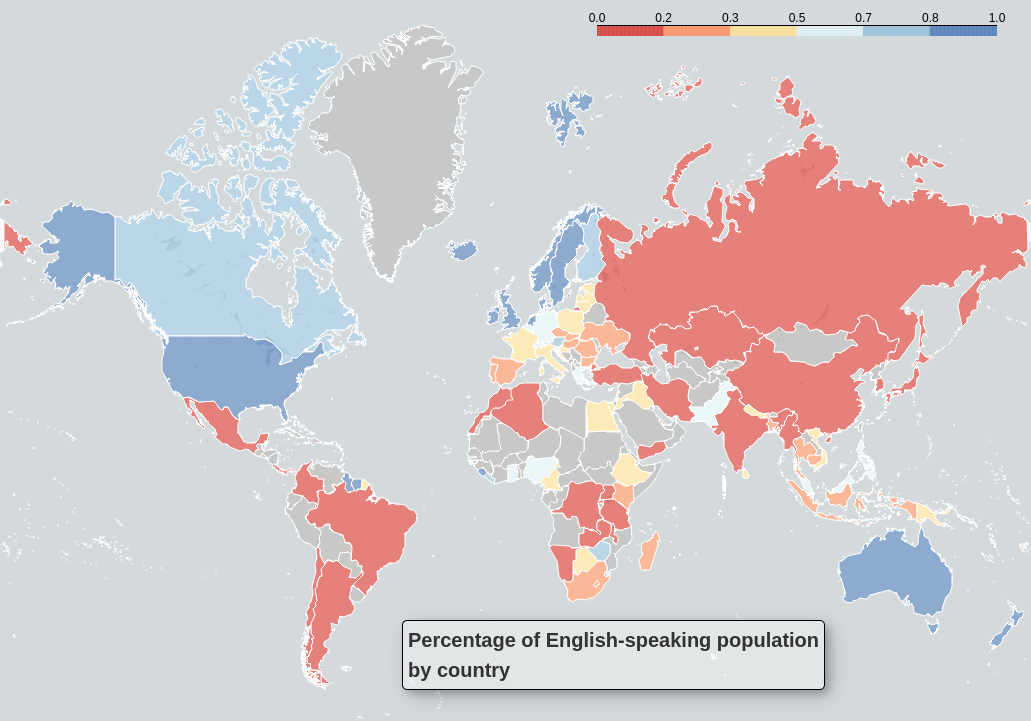

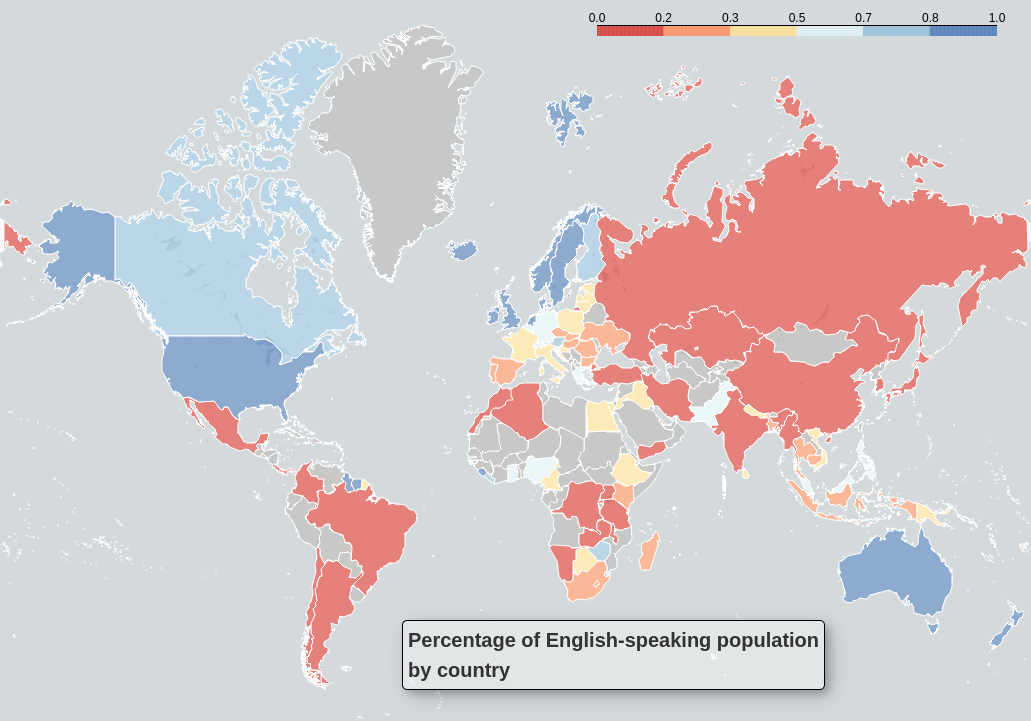

The colorblind versions of the map and of its interactive version :)! (as requested on the Reddit discussion)

The colorblind versions of the map and of its interactive version :)! (as requested on the Reddit discussion)

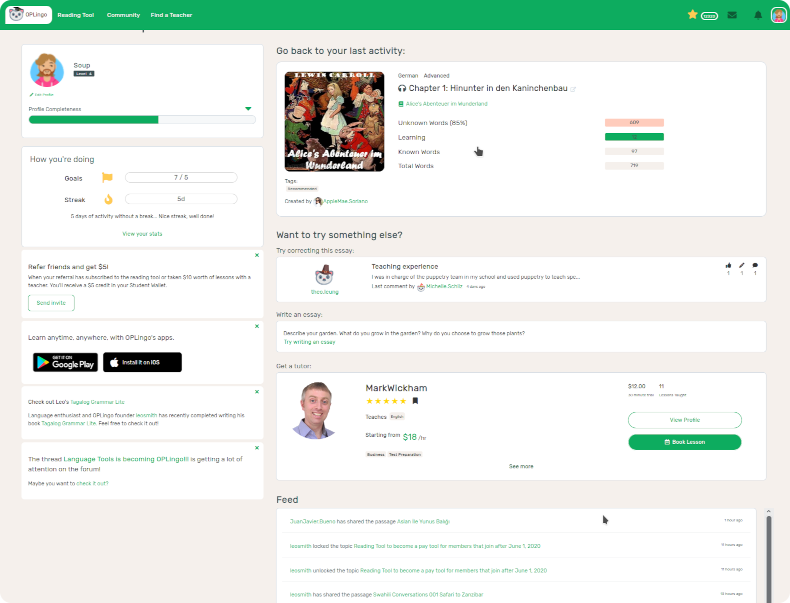

Hey OPLingo community,

As you know, we recently celebrated the relaunch of our platform. This was accompanied by the implementation of quite a few features which you might want to know about. Here's a list of some of the most prominent ones. Enjoy!

As always, please tell us if you have an idea about what we could be doing better. We are serious about being a community-led platform, and relish feedback from our users, be it positive or negative. So, if you have something to say, open the "Feedback" tab on the right of your screen, or write to us here. Looking forward to hearing from you!

The new dashboard truly lives up to its name: it provides you with an overview of what you need to know when you start a language-learning session.

Want to go back to where you left off last time? Here you go. Want to step out of your comfort zone and try a new activity? We have a few suggestions ready. Want to know what's trending in the forum? It's in the sidebar. Want to know what everyone else is doing? Look at the activity feed. With that level of control, you have everything you need to learn that language!

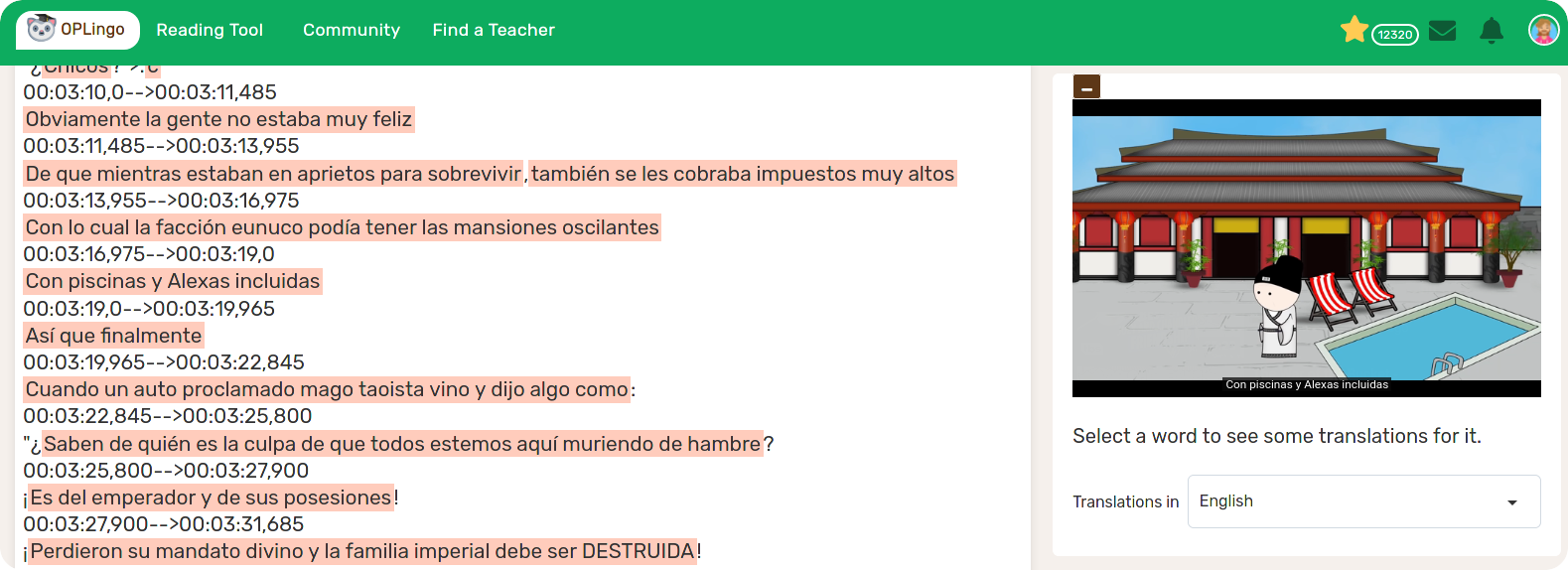

Well, this hasn't changed much, but some of the lesser known features might be unknown to you. Haven't found an interesting passage? Just import an article or an ebook you want to read into "My Passages". Prefer watching videos or listening to music? Just import a video from Youtube. And if you become a paid member you'll get more features!

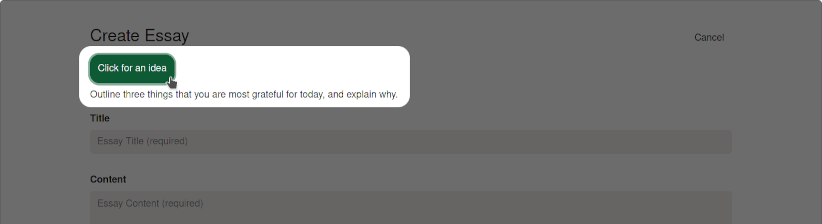

Going through writer's block? Can't think of anything to say? Don't despair, just request an idea for your essay and write away. You can write about your life, or do some creative writing, or write a thoughtful piece about world cuisine. Or just correct someone else's essay.

We know that the motivation fairy can be capricious: some days we clock in hours and hours of learning without a problem, and some days we struggle to find the energy to even open the app. Yet, it's not a secret that consistency is essential when learning languages. If that is something that you can empathise with, you're not alone. We have thought up a few ways to help you out here, by implementing some gamification features that should give the little boost that you sometimes need.

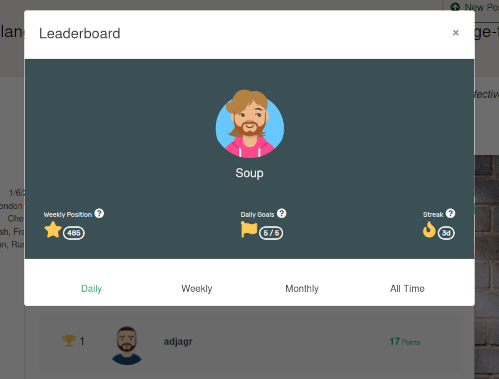

The Daily Goals are the amount of language-learning activities you want to do per day. We all learn differently, so this feature takes into account the words learned, essays written, classes taken, ...: as long as you're learning, it counts. Go set up your daily goal in your profile, but don't hesitate to go beyond your target!

There can only be one! For those of us who thrive on competition, there is a Leaderboard to keep track of who is well and truly the best. To give everyone the chance to compete, the leaderboard keeps tabs on the daily, weekly, monthly, and all-time achievements of our members.

Do you only have time to learn on the weekend? Nothing wrong with that, good job for finding time! The Streak measures consistency, but in a way that does not penalize those of us who can't connect every day: it only resets after a full week of inactivity. Let's start growing your streak today: as long as you work every week, you're good to go!

With our mobile apps, you can learn anywhere, anytime. With the relaunch, we have improved the user experience on the apps, to help make learning as intuitive, comfortable, and productive on the phone as it is on a desktop. Get your Android app, or install the iOS web app!

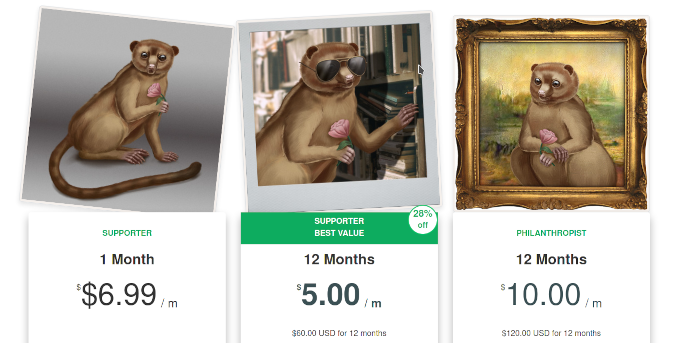

We have placed our social impact mission at the forefront of our platform (as you know, we donate all of our profits to ethical causes). Go to the Our Mission page to learn about the project we're currently funding. Upgrade to the Supporter Plan to get more features, an unlimited OPLingo experience, and to support our mission. And, if you can afford it, upgrade your plan to Philanthropist.

Have you noticed the proliferation of olingos on the platform? If that alone doesn't make your day better, I don't know what can.

If you have any questions, check out our FAQ.

What?! Another series? Yes, this one's lighter reading than the previous stuff, and has nice charts! See it as a fascinating deep-dive into the mind of a utilitarian polyglot.

An interesting thing to do when you're learning languages is to estimate the amount of people in the world you could have a conversation with. For example, leosmith, the polyglot founder of OPLingo, can converse with a third of the human race (I have it on good authority that aliens have shortlisted him for abduction, brain-washing, and subsequent employment as an ambassador to humans... he had it coming).

But what if you're just starting on your journey as a polyglot, only see languages as tools, and want to adopt the most efficient approach to your language-learning career? Surely you would want to learn the languages spoken by the most people, but also capitalize on people's proficiency in other languages. For example, if you're going to Canada, you could say that speaking English mostly covers it, so there's little need to learn French. You would lose out on a lot of things, but if you see language-learning as a purely utilitarian endeavor then this would be a valid decision.

So, how will you go about deciding which languages to learn? Well, we're going to help you out on this journey. You're welcome.

To facilitate our task, we'll assume that you speak English. Data on English proficiency worldwide is relatively easy to find (or at least it exists): this is not necessarily the case for other languages, which is why we'll be taking English as our starting point.

Let's take a data-based approach here. If one speaks English, what languages should one learn in order to maximise the amount of people one can have a conversation with?

What we want to do is the following:

The end result should be pretty close to the straightforward approach of just picking the most spoken languages one after the other, but what is interesting is to what extent the two strategies will differ.

Before we dig in, it's worth saying that this analysis needs to be taken with a grain of salt. Why? The data this is based on comes from different sources, with varying degrees of reliability, and a lot of assumptions will be made about the languages spoken in each country if data is not available. Hopefully, citing the sources and being as transparent as possible about the design of this analysis will help us circumvent most issues. The good thing is that, if you want to change something, the code and data are available: if this is your thing, your contributions are welcome!

Today we'll just deal with the first bullet point. But watch this space.

Here we go!

One would have thought that nigh-exhaustive, robust data would be readily available for English proficiency across the world - linga franca and all that - but one would be wrong. The data might be hiding somewhere, but I did not find it.

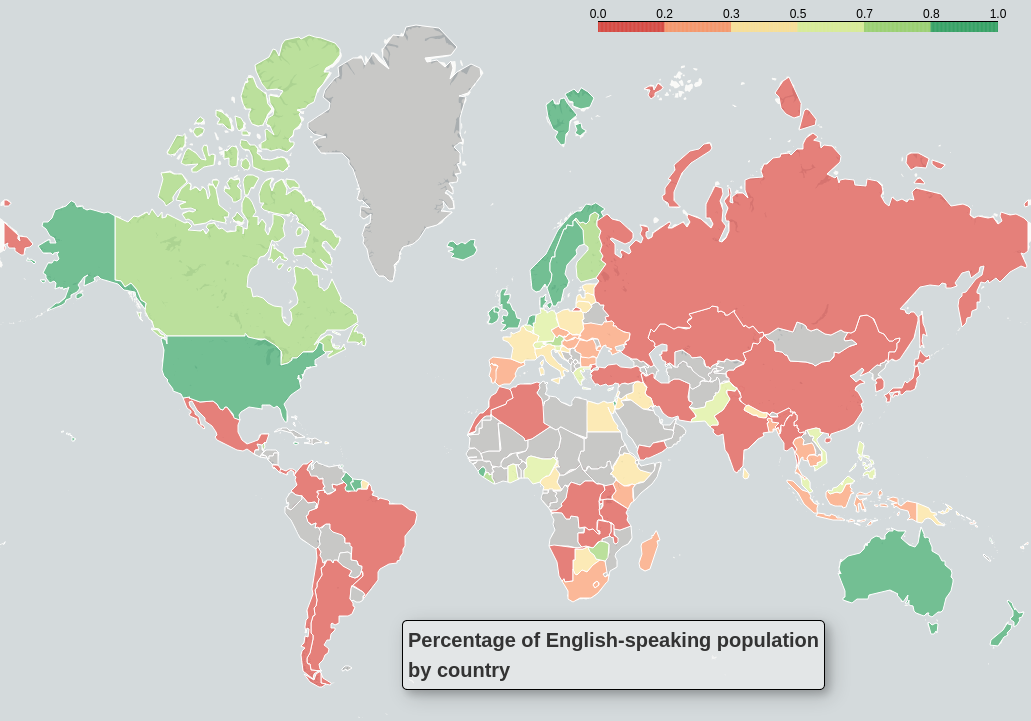

The List of countries by English-speaking population on Wikipedia is the next best thing. It gives an estimate of the English-speaking population for 130 of the world's ~200 countries. The information is not the most up-to-date, proficiency is almost entirely self-reported, the sources cited for some countries are unconvincing, some numbers are questionable, and "English-speaking" does not have a standardized meaning, but... we can definitely work with this (trust me).

Some countries with very large populations were not included in the Wikipedia list, so I had to look around for other, sometimes anecdotal, sources. I've been able to add the most robust information to Wikipedia (adding to the sum of human knowledge always feels great). In 5 cases, actual sources were not available, so I had to resort to the wisdom of crowds: random comments on discussions boards, blog posts, the direction the wind was blowing that day, etc. This wouldn't do for Wikipedia, but (corroborated) anecdotal evidence is fair game in our case, given our purposes. The total population of the ~70 countries (including currently unrecognized ones) that we have no information for represents ~800 million people, or close to 10% of the total world population. Based on some quick and dirty checks, it seems safe to say that missing data indicates proficiency levels below 10-15%.

You will notice that the Wiki page already has a map. Why the hell have we been going through this then?! Well, the map is not accurate, as it doesn't actually represent the data the page is talking about.

You might inform me of the existence of the EF English Proficiency Index, but this is also not relevant to us. The EF EPI measures the English-language skills of those who have taken the test administed by a company that sells English training: the self-selection sampling bias is huge here, so generalizing the results to wider populations and making bold inferences would be very wrong, but the number of news outlets and even officials who misconstrue the EPI as a country's ability in English is staggering. But I digress.

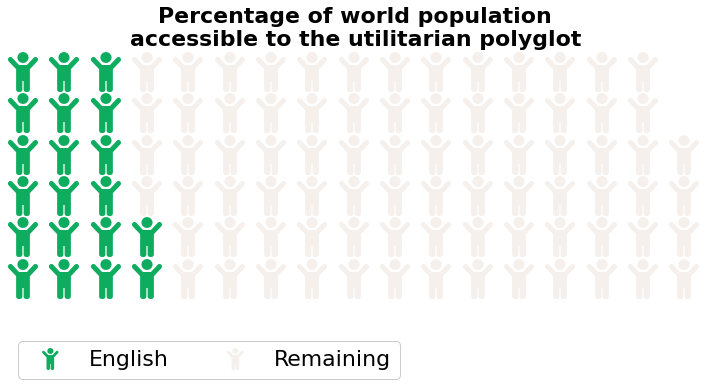

Back to our utilitarian polyglot. According to our data, English would allow one to speak to 1.5 billion people, or 20% of the world population. This is a bit higher than other estimates I've seen, but it passes our undemanding sanity check. The pictogram below will be keeping track of our progress.

Below is the map that we get from our data. The interactive version is attached and also available here, if you want to play around. Pretty neat!

A few points of interest:

What do you guys think?

Aussie.B wrote:Agree?

I couldn't agree more, and I believe the future posts in this series will be proving your point. I also like the two axes that you have identified (personality and stage in the learning process), I wonder if there are any other ones.

leosmith wrote:I don't agree with every conclusion I read, but they give me good ideas and answer questions I've had sometimes.

Hear, hear.

This is the first in a series of blog posts exploring what research says about the most effective ways of learning a language: "What does the research say? Part 1"

I recently came across a discussion about the most effective methods for learning a language. You know, the kind of discussion that is bound to happen when more than two language-learning enthusiasts enter the same room. One of the main claims in this specific debate was that the language-learning methods commonly used in language-teaching institutions - a mix of mainly grammar, rote memorization of vocabulary, and translation - must be the most effective, because otherwise they wouldn't be used in these institutions. As my reply became quite long (and rambling), I decided to make it a blog post instead.

TLDR: Judging the effectiveness of a language learning method based on its uptake by universities and language schools is ultimately a logical fallacy (known as appeal to authority), because one assumes that the behavior of renowned institutions is an adequate proxy for judging a teaching method's effectiveness. This, however, is a big assumption, with little data to back it up.

A variety of factors unrelated to the effectiveness of a specific language-learning method could be motivating language-teaching institutions to go with the traditional grammar + vocabulary + translation. Some of the main ones are inertia, misaligned incentive systems, and difficulties to measure effectiveness, and we'll be looking at those here.

This is basically resistance to change: second language acquisition has always been taught this way, that's how the teachers were taught, and that's what everyone else does.

There are many cases of such inertia leading to aberrations, throughout history and across sectors. Medicine is full of particularly famous (and graphic) examples: in keeping with the Zeitgeist, have a look at plague doctor costumes.

Or take education in general: the Finnish model of education is often presented as being close to perfect, despite diverging from how most other countries educate their children (no standardised grading, short days, no perverse quotas, etc.), but the political will to apply this has failed to manifest as of yet outside of Finland.

The inertia holds even if the new model is well-studied and proven to be superior: in the homelessness sector, the effectiveness of the approach that consists in giving homeless people accommodation before working on things like issues with drugs - Housing First - is beyond questioning, but it still remains a rare occurrence in any given country (apart from Finland maybe).

Basically, once something exists, it takes a lot of effort to change it.

In other words, "follow the money".

Incentive systems, and especially market forces, are another factor that needs to be taken into account when thinking about our quandary: language-learning is a huge industry, and a lot of powerful and well-established stakeholders (textbook publishers, universities, language schools) have strong incentives in maintaining the status quo.

This does not necessarily stem from malice. A language teacher might think grammar + vocabulary + this specific textbook might indeed be the one true way. The textbook's author might think that they're doing a service to language learners worldwide by promoting their work. The language school might think that their method works sufficiently well (more on that below), so why experiment with new ones? A language-learner who just went through a language school's program is likely to convince themselves that they chose the best option.

Of course, there can be less-than-altruistic factors at play as well. For example, the textbook publishing is an oligopoly known for its predatory practices. Language-teaching institutions could be said to have an incentive to make their study program last longer (so it costs more).

But, however good the stakeholders' intentions, the result is the status quo being maintained.

A paradigm shift is especially hard to implement if the effectiveness of the different methods is difficult to measure. Mind you, even those methods that are easily measurable will not dominate a field easily (bloodletting was the most common medical practice for two millennia, even though it was harmful to the vast majority of patients). But the lack of evaluation definitely doesn't help.

Learning a language is a perfect example of that: most people are not that motivated to learn, most of the motivated ones will rarely use their target language, most of those who do will take years to get proficient and will be severely overestimating their proficiency up to that point. Add to that an unholy amount of confounding factors that are difficult to fully take into account.

Imagine method 1. It takes 6 months, it's cheap, takes place online, and 5% of those who start this method (including those who drop out) have a B2 level one year after.

Now imagine method 2. It takes two years (so learners have ample time to expose themselves to their target language outside of classes and they do, through their own volition, because that's what they're enthusiastic about), it's taught in a school that is located in the target-language-speaking country (read: free immersion), it's very expensive (so most everyone who starts it is already more motivated than the average learner and has a strong incentive to not drop out, so as to avoid wasting money). 40% of those who start method 2 are B2-level one year after.

Is method 2 better than method 1? There is no way to tell, because method 2 starts with much more motivated learners and reaps benefits - for free - from its location in the target country and the learners' free time. Maybe simply going to the target country for a year would yield the same result. Is method 2 worse than method 1? Method 1 sure seems much more accessible to the average person, but apart from that it's difficult to say. One thing you can tell for sure is that more research is needed, so that we can compare apples to apples.

Again, this blog post is not interested in claiming that the standard language-learning methods are wrong (we do not push any specific method at OPLingo), it simply aims to encourage taking a more evidence-based view of this space.

Is it possible that the most common language-learning methods are indeed the best? Yes, it is possible. Do they work? They most certainly do, at least to some extent. But has their superiority been examined in a critical, scientific way? Well, not really. And let me tell you that the research can be quite surprising (take this with a handful of salt before I have the chance to write more about it, but, as a foretaste, there is some evidence that learning grammar can be counterproductive to learning a language, for example).

In the blog posts in this series to come, we'll look at the existing research on the most effective second language acquisition methods. They might have their own biases or research design flaws, which we'll try to identify. In any case, now is a good time to be looking at this research, as the pandemic has given a second wind to new developments in education, at the same time as an opportunity for change.

We have been working on this for a while, and wanted to tell you all about it:

We are officially relaunching Language Tools as OPLingo!

We'd like to say thanks to all those who contributed, by helping us to come up with a new name, by talking about us in their communities, by telling us what they wanted from the platform, by subscribing to LT, and by simply learning languages with us. Tomorrow (or later today, depending on where you are), LanguageTools.io will become OPLingo.com. Don't worry, you will be able to continue as normal, as your accounts, data, and progress will be seamlessly transferred. You won't even have to type the new address, as you'll be automatically redirected to the new website.

Why relaunch? We want to...

We also want you to know something important: we need your support during this time. We literally cannot do this without you. Please consider helping us out by giving feedback, by spreading the word, by liking our posts on social media, by helping us keep our community forum active, by sharing new passages for people to read, or by writing essays about your day. Basically, keep being yourself, but be yourself even harder. In the coming days and weeks, we will keep you up-to-date about our latest posts and communication efforts, please visit those links and back us up.

Thanks so much again, and get ready for OPLingo!

Hey team,

This is the continuation (and end) of the Language(s) of Science series that we started here. It's a long one, so let's dive right into it.

Today, English is the dominant language of science. There are many factors - political, economic, social, or regulatory - that help explain this phenomenon. The geopolitical dominance of the British Empire and then of the United States in the last few centuries gave the language a head-start, and a momentum. Rich English-speaking countries are some of the most prolific in terms of scientific output. The quasi-totality of the most influential scientific journals are English-language, and an oligopolistic academic publishing sector reinforces a monolingual scientific communication. English might be the most widely spoken language in the world, at more than 1 billion people. The "publish or perish" culture, where funding and tenure are conditional on publication performance above all else, and the incentive systems that result from this lead scientists to write in the language that will increase the likelihood of the article getting published, reaching a large readership, and garnering citations.

Intentionally or not, the whole system seems to be clamouring for English to be the language in which science is done.

The existence of a lingua franca in science has undeniable advantages. It removes all linguistic barriers – except one – to communicating and accessing scientific developments the world over. It underpins the internationalisation of universities, which broadens the education and career prospects of students and professors worldwide. It further standardizes the production of knowledge, which facilitates organization of and access to knowledge.

The factors listed above, be they implicit or explicit, could be described as high-level characteristics of the global system we inhabit, only tenuously related to science. However, as desirable as the resulting advantages are, their corollaries are no less hypothetical, if much less researched.

A bird-eye look at the dominance of English yields some striking insights.

Depending on the scientific field, and the data one looks at, up to 97% of scholarly publication can be in English, with hard sciences being more monolingual than humanities. Even in countries with a large scientific output, articles are written in English-only, and increasingly so. Journals that used to be plurilingual are increasingly becoming English-only. Non-English-language journals are further hidden from view by their exclusion from leading journal indexes. Scientific terminology often remains confined to English, making other languages potentially inadequate for doing science. The assumption that all important information is in English biases understanding of science (the flu virus H5N1, which could have been a major pandemic, famously went unnoticed for months because it was first reported in Chinese, not in English).

At a time where science is suffering from the replication crisis and a crisis of trust, it is desirable to facilitate discussion around each and every publication, and few languages have more speakers than English. But then again, a monolingual research produced for an exclusive (if heterogeneous) readership provides for little diversity in terms of perspective, and the perverse outcomes of an English-only science weaken the local nature of research communities and remove research cultures from the very contexts that nurtured them.

English is so deeply ingrained in the metrics of science that it is more a requirement than a choice.

Because the costs of translation services are prohibitively high for most scientists, few of them can afford to produce two versions of their paper, so they often choose to write in English only. This includes humanities: researchers who are interested in fundamentally local topics (the Quechua language, or Bantu traditions, or Spanish history) are increasingly compelled to publish their work in English. Those scientists who can afford producing their papers both in English and their local language need to contend with bans on dual publication enforced by most journals, which forbid papers to be republished elsewhere.

This situation is also profoundly unfair, because proficiency in English is not evenly distributed and is dependent on socioeconomic status: an English-only science provides a massive advantage to those who have English as their first language, or who have been able to access high-quality education in English.

And this disadvantage has a compound effect. Those with a poorer level of English are less likely to choose to study science, are more likely to lag behind, take longer to process their English-language material, incur more costs and take longer to produce research, are refused publication because of language mistakes, are more likely to face prejudice because of their poorer writing, are less likely to have good metrics and get funding, can even get snubbed in favor of their Anglophone collaborators in media. The list goes on. The effect is that less people do science, and a large majority of scientists work in a language they're less confident in, while those who choose to work in a language other than English have trouble making themselves visible.

An English-first science impedes the development of national and regional research communities and cultures, limits both the quantity and quality of research, allows loss of knowledge, and reduces science's diversity. While the final balance is unclear, it is undeniable that global research does not only stand to gain from a lingua franca.

Despite the criticisms presented here, the dominance of English in science is unlikely to be imperilled in the foreseeable future, because too many feedback loops within the systems that science exists in buttress this supremacy.

Of course, some mechanisms push back against this, directly or indirectly. Open-access journals, which are becoming increasingly commonplace, have many advantages over traditional journals and these qualities indirectly make the existence of non-English journals more viable. Machine translation, while still being inadequate for translating complex academic language, is constantly improving and lowering translation costs. Some of the largest journal indexes have started accepting non-English-language journals, and non-English indexes (like SciELO) are gaining ground, which in turn fuels their advocacy for a more diverse science.

But further efforts, big and small, are required. While there has not been enough discussion to identify what these could be, existing literature seems to converge on some ideas. National policies that financially support scientists to learn English, translate their work, and publish it could strengthen national, and global, research. Dual publishing bans, which benefit journals at the expense of the community at large, need to be regulated away. Anglophone journals should make efforts to welcome multilingual research, and the metrics that scientists are evaluated against need to decouple themselves from English. The negative effects of an English-first science need to be more thoroughly researched. Finally, the individual experiences of those who have had to abandon science, who struggle against a system geared against them, experiences that are deeply human, harrowing, and relatable, need to become a focus of popular science writing, and achievements need to be celebrated.

To quote another article: "The language we use when we speak science is as important as any other part in a methods section and should be deliberate and fair."

Hey Michel, thanks for your contribution.

wrote:Even in latin languages countries - nobody but a few biologists use or know the latin names of living beings.

The proposal is directed mainly at biologists (the original paper appears in the Communications Biology journal). Also, it bears repeating that scientific names, despite being known colloquially as Latin, are not necessarily in Latin.

wrote:Many of the indigenous names are not unique. Take for example this root called witloof in Dutch, endive in France and chicon in French speaking Belgium. I'm sure there are many such examples around the world.

The first article I've linked, and the paper itself, explicitly mention uniqueness of names as being a desirable feature that the current system strives for, but does not always have (the authors offer the example of 20 species being named after the same missionary). They express their hope that a renaming, among other things, would help make scientific names more unique.

wrote:Another point is those indigenous languages have their own scripts, should biologists know all the scripts?

I don't think this is requested in any of the articles or the paper itself. Surely this is not required to respect the spirit of the proposal?

Hey team,

Hope you guys missed the blog posts (and sorry for the delay). I've recently come across a few thought-provoking pieces about the place that language occupies in science. The pieces are connected, in a way, but discussing them together would make for a very long post. So we'll talk about the scientific names of living things in part 1 today, and question the necessity of a lingua franca in science tomorrow. Let's start.

Since the 18th century, all living things are given a two-part name: think Homo Sapiens (humans), Escherichia Coli (a bacterium), or Canis familiaris (dogs). Despite these scientific names being colloquially known as Latin names, they can be derived from any language, be a homage to a person, or even a joke. There are valid reasons for the prevalence of this naming system: it's adopted worldwide, and allows for short and (mostly) unique names. As far as scientific codification goes, the system does the job.

However, a proposal has recently been put forward to restore Indigenous names within the scientific nomenclature. More and more often, Indigenous Peoples are consulted when naming, or renaming, new species (or landmarks). What the present proposal asks, however, is for the Indigenous names to be systematically, and even retroactively, included into the scientific names (turning Diospyros virginiana into Diospyros pessamin, for example).

From the paper: "for Indigenous Peoples, [names] may also embody history, a sense of place and a right to belong". And "the changes we propose would herald an important step in the affirmation of Indigenous People’s contribution to nomenclature and knowledge"

Support for the idea has been voiced before and the arguments are sound. The shift would acknowledge that Indigenous names predate scientific ones by centuries. It would motivate scientists to recognise and draw from the age-old knowledge encoded within Indigenous names (an unsurprising fact, given how indispensable that information was and still is to the survival and thriving of Indigenous People's within their ecosystems). And it would celebrate the beautiful connection with nature that defines so much of indigenous languages and cultures.

Is there a downside to this proposal? There seems to be little, if any: the underlying two-part naming system is left intact and the authors acknowledge that the number of species that would have to be renamed is small; the sum of human knowledge stands to grow, as does recognition of indigenous cultures; and the resulting names will be less Western-centric.

In addition to the proposal's inherent merits, it also benefits from a favorable social context, which previous attempts didn't have, so it might well garner enough support to get implemented. What are your thoughts about this?

Hey @Kirsti.Steibel,

This is such a deep subject that calling it a rabbit hole would be an understatement (pretty sure I saw multiple foxes and a sasquatch in there).

I want to do it justice though, please bear with me.

Hey zakenney, thanks for the tip, they seem to be doing cool work indeed! Found similar efforts in other religions as well, I’ll be sure to include this into the post about non-tech-based conservation efforts, cheers!

We obviously all interpret history, geopolitics, culture, etc., differently, and extrapolate differently, but I wouldn't say that such an extreme scenario is likely, for a number of factors.

Great post!

leosmith wrote:There are still obvious problems though. They are only listing 45m Filipino speakers. I don’t know where that number came from – there are 110m Filipinos, and probably 99% of them speak Filipino. Oh well; at least they’ve made some progress.

I found this weird, looked more into it. The table has been copied from SIL's 2019 edition of Ethnologue (paywalled), which apparently makes a distinction between Tagalog and Filipino, where Tagalog has 24 million native speakers and Filipino has 45 million L2 speakers.

Now I don't know much about this, but Wikipedia seems to say that Tagalog and Filipino are synonyms, in practice. The wiki page for Tagalog counts both numbers given above (so 79M total), while the one for Filipino only counts L2 speakers. I'd wager that the SIL table has not been correctly copied, basically: if Tagalog and Filipino are seen as being equivalent, then the language would have 79 million speakers and come in at the 23rd position.

There was some discussion about the Tagalog/Filipino equivalence on this page in 2018, but it was never resolved. I think it's safe to edit the page.

Michel wrote:Very interesting. Thank you for the links.

I will probably never learn one of those endangered languages.

Cheers!

That's the problem with endangered languages: there aren't enough incentives to learn them (there can even be strong disincentives). I see you're from Belgium though: chances are you know people who speak an endangered language, as a (very unscientific) estimate based on this data tells me that 5-10% of the population in your country speaks one. I'm from neighbouring France, where Breton, at least, is having a strong revival.

Hey team,

Time for another post. Today, we're looking at how people use technology to help endangered languages. Technological solutions are unlikely to suffice for saving what amounts to half of the 7,000 languages spoken on the planet, and we'll look at other approaches in the future, but it is undeniable that technology has a role to play. Here are a few examples of such solutions, developed by whole organizations or one-person teams.

Hope you're all having a nice weekend!

Hey Kirsti, I'd wager this feeling is quite common for people who speak multiple languages (even those who speak a single language often yearn for the right word to describe their specific feeling). Comes with the human condition, it seems :).

I know about a few studies into this, it's an interesting topic. I'll look into it a bit more and dedicate next week's blog post to your comment :)

Hey team,

Welcome back to our weekly thread about all things language. First, we have a small change to announce: these blog posts won't be weekly anymore. "What? But you literally just said" -- yes, I know. But we thought that shorter posts with a common theme every other day would be easier to process and more conducive to discussions than weekly digests. Ironic, that a digest would be indigestible...

Anyway, here are today's articles:

What are your thoughts?

Sounds great, I'll check it out! Start a thread in the forum if you come across something like that in the future, at least that way I won't miss it :)

Kirsti.Steibel wrote:Thank you for this interesting blog. Among celebrating days there was the European Day of Language on 26 September.

Thanks! Don't know how I missed that one...

Animefangirl wrote:China has already banned dialects in a number of areas. Inner Mongolia is simply the latest. Their protests won't have much effect, I'm afraid.

Kirsti.Steibel wrote:It's a pity dialects in China are not seen as a resource.

You guys are right, unfortunately. A telling quote from the article:

The move is similar to what has happened in other ethnic minority areas in China. In Tibet and Xinjiang, the primary language of instruction in such schools has become Mandarin, and the minority language is a language class.

The protests are not expected to have an effect, and I imagine that the protesters know it full well...

Hey there,

I'm Soup, the (relatively) new product manager at Language Tools (soon to be OPLingo). Among other things, I'll be publishing a blog post once a week with the most interesting stuff about language and languages that I have the chance of coming across. I'd be happy if I could contribute to discussion here. Any feedback is welcome. You'll see me around quite a lot on the forum, as Leo and the team start announcing exciting news in the coming weeks.

Now that presentations are done, let's get to it.

First weekly post ever! Hope it leads to some great conversations, and be sure to share any feedback with me.

Cheers,

Soup

Hey Valeria,

This is a really interesting topic I think.

As I was starting to learn English in a serious way, ten years ago now, I noticed how people online gradually started saying "she" about a hypothetical person instead of "he", and then, more recently, how it started shifting to "they". Similarly, in French, the écriture inclusive is something that became quite prevalent recently: instead of writing les amis/les amies, you can write les ami-e-s. In Spanish, you can write lxs amigxs instead of los amigos/las amigas.

These are all examples of gender-neutral language [0], which is itself a subset of inclusive language [1]. The wiki pages in English and Portuguese about this are very poor compared to the ones in French or in German, for example, but they're informative nonetheless. And yes, it seems to be a new development, insofar as it's becoming socially accepted, and even expected in some circles, and is becoming the norm in official communication.

[0]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gender-neutral_language

[1]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inclusive_language